The long history of Zionist proposals to ethnically cleanse the Gaza Strip

Ethnic cleansing or "transfer" is an intrinsic part of Zionism's early history, and has remained an essential feature of Israeli political life. More recently

Senior Israeli leaders, including Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, are again publicly advocating the ethnic cleansing of the Gaza Strip. Their proposals are being presented as voluntary emigration schemes, in which Israel is merely playing the role of Good Samaritan, selflessly mediating with foreign governments to find new homes for destitute and desperate Palestinians. But it is ethnic cleansing all the same.

Alarm bells should have started ringing in early November when U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and other Western politicians began insisting there could be “no forcible displacement of Palestinians from Gaza.” Rather than rejecting any mass removal of Palestinians, Blinken and colleagues objected only to optically challenging expulsions at gunpoint. The option of “voluntary” displacement by leaving residents of the Gaza Strip with no choice but departure was pointedly left open.

Ethnic cleansing, or “transfer” as it is known in Israeli parlance, has a long pedigree that goes back to the late-nineteenth-century beginnings of the Zionist movement. While the early Zionists adopted the slogan, “A Land Without a People for a People Without a Land,” the evidence demonstrates that, from the very outset, their leaders knew better. More to the point, they clearly understood that the Palestinians formed the main obstacle to the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. This is for the simple reason that, to them, a “Jewish state” denotes one in which its Jewish population acquires and maintains unchallenged demographic, territorial, and political supremacy.

Enter “transfer.” As early as 1895, Theodor Herzl, the founder of the contemporary Zionist movement, identified the necessity of removing the inhabitants of Palestine in the following terms: “We shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it any employment in our own country … expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly.” David Ben-Gurion (née Grün), Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, and later Israel’s first prime minister, was more blunt. In a 1937 letter to his son, he wrote: “We must expel the Arabs and take their place.”

Writing in his diary in 1940, Yosef Weitz, a senior Jewish National Fund official who chaired the influential Transfer Committee before and during the Nakba (“Catastrophe”), and became known as the Architect of Transfer, put it thus: “The only solution is a Land of Israel devoid of Arabs. There is no room here for compromise. They must all be moved. Not one village, not one tribe, can remain. Only through this transfer of the Arabs living in the Land of Israel will redemption come.” His diaries are littered with similar sentiments.

The point of the above is not to demonstrate that individual Zionist leaders held such views, but that the senior leadership of the Zionist movement consistently considered the ethnic cleansing of Palestine an objective and priority. Initiatives such as the Transfer Committee, and Plan Dalet, initially formulated in 1944 and described by the pre-eminent Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi as the “Master Plan for the Conquest of Palestine,” additionally demonstrate that the Zionist movement actively planned for it. The 1948 Nakba, during which more than four-fifths of Palestinians residing in territory that came under Israeli rule were ethnically cleansed, should, therefore, be seen as the fulfillment of a longstanding ambition and implementation of a key policy. A product of design, not of war (historical Christmas footnote: the Palestinian town of Nazareth was spared a similar fate only because the commander of Israeli forces that seized the city, a Canadian Jew named Ben Dunkelman, disobeyed orders to expel the population, and was relieved of his command the following day).

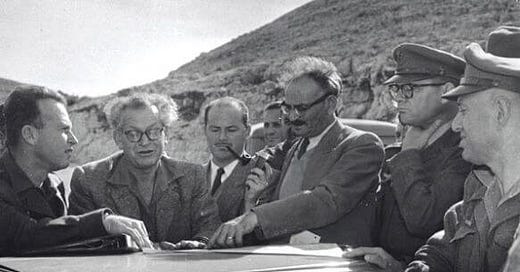

That the Nakba was a product of design is further substantiated by the Transfer Committee’s terms of reference. These comprised not only proposals for the expulsion of the Palestinians but, just as importantly, active measures to prevent their return, destroy their homes and villages, expropriate their property, and resettle those territories with Jewish immigrants. Weitz, together with fellow Committee members Eliahu Sassoon and Ezra Danin, on June 5, 1948, presented a three-page blueprint, entitled “Scheme for the Solution of the Arab Problem in the State of Israel,” to Prime Minister Ben-Gurion to achieve these goals. According to leading Israeli historian Benny Morris, “there is no doubt Ben-Gurion agreed to Weitz’s scheme,” which included “what amounted to an enormous project of destruction” that saw more than 450 Palestinian villages razed to the ground.

The understandable focus on the expulsions of 1948 often overlooks the fact that ethnic cleansing remains incomplete unless its victims are barred from returning to their homes by a combination of armed force and legislation, and thereafter replaced by others. It is Israel’s determination to make Palestinian dispossession permanent that distinguishes Palestinian refugees from many other war refugees.

After 1948, Israel put out a whole series of fabrications to shift responsibility for the transformation of the Palestinians into dispossessed and stateless refugees onto the Arab states and the refugees themselves. These included claims that the refugees voluntarily left (they were either expelled or fled in justified terror); that Arab radio broadcasts ordered the Palestinians to flee (in fact, they were encouraged to stay put); that Israel conducted a population exchange with Arab states (there was nothing of the sort); and the bizarre argument that because they’re Arabs, Palestinians had numerous other states while Jews have only Israel (by the same logic, Sikhs would be entitled to seize British Columbia and deport its population to either the rest of Canada or the United States). More importantly, even if uniformly substantiated, none of these pretexts entitles Israel to prohibit the right of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes at the conclusion of hostilities. It is, furthermore, a right that was consecrated in United Nations General Assembly resolution 194 of December 11, 1948, which has been reaffirmed repeatedly since.

Ethnic cleansing after 1967

In 1967, Israel seized the remaining 22 percent of Mandatory Palestine — the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Gaza Strip. Depopulation in these territories operated differently than in 1948. Most importantly, Israel, in addition to prohibiting the return of Palestinians who fled hostilities during the 1967 June War, and encouraging others to leave (by, for example, providing a daily bus service from Gaza City to the Allenby Bridge connecting the West Bank to Jordan), conducted a census during the summer of 1967 . Any resident who was not present during the census was ineligible for an Israeli identity document and automatically lost their right of residency.

As a result, the population of these territories declined by more than twenty percent overnight. Many of those thus displaced were already refugees from 1948. Aqbat Jabr Refugee Camp near Jericho, for example — until 1967, the West Bank’s largest — became a virtual ghost town after almost all its inhabitants became refugees once again in Jordan. So many Palestinians from the Gaza Strip ended up in Jordan that a new refugee camp, Gaza Camp, was established on the outskirts of Jerash. The occupied Palestinian territories would not recover their 1967 population levels until the early 1980s.

Within the West Bank, there were also cases of mass expulsion. These included the town of Qalqilya, which was additionally slated for demolition but to which its residents were later permitted to return. Those of ‘Imwas (the Biblical Emmaus), Bayt Nuba, and Yalu in Jerusalem’s Latrun salient were less fortunate. They were summarily expelled (many today live in Ramallah’s Qaddura Refugee Camp), their villages demolished and annexed to Israel, and replaced by Canada Park, so named because the project was completed with donations from the Canadian Jewish community. Within Jerusalem’s Old City, the historic Mughrabi Quarter, abutting the Haram al-Sharif, was summarily razed to make way for a plaza astride the Wailing Wall. With many residents given only minutes to evacuate their homes, several were killed when the bulldozers went to work. According to Eitan Ben-Moshe, an engineer who oversaw the atrocity, “We threw out the wreckage of houses together with the Arab corpses.”

Depopulation through administrative rule

In subsequent years, Israel employed all kinds of administrative shenanigans to further reduce the Palestinian population of the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Until the 1993 Oslo Accords, for example, an exit permit from Israel’s military government was required to leave the occupied territory. It was valid for only three years and thereafter renewable annually for a maximum of three additional years (for a fee) at an Israeli consulate. If a Palestinian lost an exit permit or failed to renew an exit permit prior to its expiration for any reason (including bureaucratic foot-dragging), or couldn’t pay the renewal fee, or failed to return to Palestine prior to its expiration, that Palestinian automatically lost residency rights. Separately, Israel, over the years, deported numerous activists and community leaders, primarily to Jordan and Lebanon. During the late 1960s and 1970s, it also exiled Gaza Palestinians accused of resisting the occupation, along with their families, to prison camps in the occupied Sinai Peninsula. Among those who spent time there was the iconic Palestinian leader Haidar Abdel-Shafi.

A particularly notable case of administrative deportations occurred in 1992 after Israeli special forces botched an operation to rescue an Israeli soldier who had been seized by Hamas to exchange him for their imprisoned leader, Shaikh Ahmad Yasin. Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin ordered the summary deportation of approximately 400 Palestinians, many of them prisoners affiliated with Hamas and Islamic Jihad (PIJ), none accused of involvement in the incident that led to Rabin’s frenzied rage.

In contrast to previous deportations, which were considered permanent, these were for one- and two-year terms. In its rush to carry out the deportations under cover of night, Israel expelled a number of Palestinians who were not on its list and left behind others who were. Needless to say, the mass expulsion was, as always in such matters, approved by Israel’s High Court of Justice after minor modifications. It ruled, among other things, that this was not a collective deportation but rather a collection of individual deportations. Perhaps more significantly, the deportees were stuck in an inhospitable no-man’s land, Marj al-Zuhur, because Lebanon refused to facilitate the deportations by receiving them. During their involuntary residence in Marj al-Zuhur, assistance came primarily from Hezbollah, and it was during this period that relations between Hamas, PIJ, and Hezbollah were solidified.

Israel’s strategies to ‘thin’ Gaza’s population

With the focus in recent years on the intensified campaigns of ethnic cleansing in the West Bank, it is often forgotten that, for decades, the primary target for depopulation was the Gaza Strip, particularly its refugee population, which accounts for approximately three-quarters of the territory’s residents. Even before it occupied Gaza in 1967, Israel regularly promoted initiatives to achieve the “thinning” of its refugee population, with destinations as far afield as Libya and Iraq. Not without reason, Israel’s leaders felt uncomfortable with the presence of so many ethnically cleansed Palestinians within walking distance of their former homes. After 1967, it encouraged Palestinian emigration from the Gaza Strip to not only foreign countries but also the West Bank.

“Transfer,” often presented as the encouragement of voluntary emigration either by providing material incentives or making the conditions of life impossible, has become increasingly mainstreamed in Israeli political life.

In 1969, Israel even devised a scheme to send 60,000 Palestinians from the Gaza Strip to Paraguay with offers of lucrative employment. The plan was negotiated between Paraguay’s military dictator Alfredo Stroessner and Mossad, the Israeli foreign intelligence agency. It was, of course, purely coincidental that, shortly thereafter, Mossad discovered it no longer had the resources to hunt Nazi fugitives in Paraguay, which had been one of their destinations of choice. The scheme was discontinued when several of its victims, upon realizing the promise of a new life of comfort was all a sham, shot up the Israeli embassy in Asuncion, killing one of its staff.

‘Transfer’ and Gaza today

In the decades since, “transfer,” often presented as the encouragement of voluntary emigration either by providing material incentives or making the conditions of life impossible, has become increasingly mainstreamed in Israeli political life. In 2019, for example, a “senior government official,” quoted in the Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz, expressed a willingness to help Palestinians emigrate from the Gaza Strip.

Mass expulsion has been gaining its share of adherents as well, and it is a position that is today represented within Israel’s coalition government. As has the idea that “transfer” should include Palestinian citizens of Israel — Avigdor Lieberman, for example, who was Israel’s Minister of Defense several years ago, is an advocate of not only emptying the West Bank and Gaza Strip of Palestinians but of getting rid of Palestinian citizens of Israel as well. As one might expect from a minister who was in charge of the Israeli military, he is also an advocate of “beheading” disloyal Palestinian citizens of Israel with “an axe.”

Against this background, Israel saw the attacks of October 7 as not only a threat but also as an opportunity. Fortified with unconditional U.S. and European support, Israeli political and military leaders immediately began promoting the transfer of Gaza’s Palestinian population to the Sinai desert. The proposal was enthusiastically embraced by the United States and by Secretary of State Antony Blinken in particular. Hopelessly out of his depth when it comes to the Middle East, as ever, he appears to have genuinely believed he could recruit or pressure Washington’s Arab client regimes to make Israel’s wish a reality. Given Egyptian strongman Abdelfattah al-Sisi’s economic troubles, the fallout of the Menendez scandal, and the looming Egyptian presidential elections, it was suggested to him by the Washington echo chamber that it would take only an IMF loan, debt relief, and a promise to file away Menendez to bring Cairo on board. As so often when it comes to the Middle East, Blinken, armed only with Israel’s latest wish list, didn’t have a clue his indecent proposal would be categorically rejected, first and foremost by Egypt.

THANK YOU! to Everyone Who Contributed to our 1st Ever Fundraiser for the Art of Liberty Foundation! As of January 2nd we have raised $34,568 or 69% of our $50,000 goal! Donations are still coming in via postal mail and the internet so we will announce the final total next week BUT I wanted to thank everyone who contributed and/or went “Paid” on Substack. We simply couldn’t do this work without the folks who support us financially! It is so very much appreciated!! Happy New Year to All!! - Etienne