John Mauldin: Supercycle of Debt

Today we’ll start wrapping up the series by discussing the Debt Supercycle. I think we’ll probably need a few weeks, but this is important. I don’t want to rush through it.

by John Mauldin

We have been looking at big historical/economic/political cycles for the past two months. We reviewed Neil Howe’s Fourth Turning concept, then George Friedman’s twin US institutional and socioeconomic cycles, then Peter Turchin’s “cliodynamics” concept, and then Ray Dalio’s Big Cycle.

None of these theories exclude the others. It is quite possible they are describing the same events through different lenses. In any case, they help us understand the times we live in. They are neither predictive nor prescriptive, but descriptive. They look back through history and try to interpret the past to help us understand what might happen in the future. I think all are at least partially correct. That’s disturbing… because in various ways, each points to serious global problems in the next few years.

Today we’ll start wrapping up the series by discussing the Debt Supercycle. I think we’ll probably need a few weeks, but this is important. I don’t want to rush through it.

Time-Traveling Money

Debt has a defined sequence: The lender and borrower agree on terms, the loan is funded, the borrower repays according to a schedule, eventually pays the full amount, then it’s over. Often the parties move on to more such deals, then others, then others… in an almost (dare I say it?) cyclical fashion.

As I’ve said many times, debt isn’t inherently bad. It’s an efficient way to finance new productive capacity. This helps the economy grow and raises living standards for everyone. But debt is also easily misused, and that’s where it causes trouble. In fact, we have seen throughout history where debt has been used far more than was prudent, especially by governments, and you get a debt crisis for an individual company or country.

Professors Ken Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart described this process for governments in their magisterial book, This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. I think it is one of the most important books of the last 20 years. I have reviewed it extensively in the past and did a published interview with both Rogoff and Reinhart.

What I wrote in my 2011 letter The Beginning of the Endgame is the perfect set-up for dealing with the debt and deficits of the US (and then a possible survey of other debt-burdened economies).

“The lesson of history, then, is that even as institutions and policy makers improve, there will always be a temptation to stretch the limits. Just as an individual can go bankrupt no matter how rich she starts out, a financial system can collapse under the pressure of greed, politics, and profits no matter how well regulated it seems to be. Technology has changed, the height of humans has changed, and fashions have changed.

“Yet the ability of governments and investors to delude themselves, giving rise to periodic bouts of euphoria that usually end in tears, seems to have remained a constant. No careful reader of Friedman and Schwartz will be surprised by this lesson about the ability of governments to mismanage financial markets, a key theme of their analysis.

“As for financial markets, we have come full circle to the concept of financial fragility in economies with massive indebtedness. All too often, periods of heavy borrowing can take place in a bubble and last for a surprisingly long time. But highly leveraged economies, particularly those in which continual rollover of short-term debt is sustained only by confidence in relatively illiquid underlying assets, seldom survive forever, particularly if leverage continues to grow unchecked.

“This time may seem different, but all too often a deeper look shows it is not. Encouragingly, history does point to warning signs that policy makers can look at to assess risk—if only they do not become too drunk with their credit bubble-fueled success and say, as their predecessors have for centuries, ‘This time is different.’

“[Back to my voice] Sadly, the lesson is not a happy one. There are no good endings once you start down a deleveraging path. …much of the entire developed world is now faced with choosing from among several bad choices, some being worse than others.

“And this is key. Read it twice (at least!):

“Perhaps more than anything else, failure to recognize the precariousness and fickleness of confidence—especially in cases in which large short-term debts need to be rolled over continuously—is the key factor that gives rise to the this-time-is-different syndrome. Highly indebted governments, banks, or corporations can seem to be merrily rolling along for an extended period, when bang! — confidence collapses, lenders disappear, and a crisis hits.

“Economic theory tells us that it is precisely the fickle nature of confidence, including its dependence on the public’s expectation of future events, which makes it so difficult to predict the timing of debt crises. High debt levels lead, in many mathematical economics models, to ‘multiple equilibria’ in which the debt level might be sustained—or might not be. Economists do not have a terribly good idea of what kinds of events shift confidence and of how to concretely assess confidence vulnerability.

“What one does see, again and again, in the history of financial crises is that when an accident is waiting to happen, it eventually does. When countries become too deeply indebted, they are headed for trouble. When debt-fueled asset price explosions seem too good to be true, they probably are. But the exact timing can be very difficult to guess, and a crisis that seems imminent can sometimes take years to ignite.”

The term Debt Supercycle was first used by Tony Boeckh of The Bank Credit Analyst (in the late ’60s) and further explored by my good friend Martin Barnes when he was editor. The concept has been refined over time, but the term still fits. There seems to be a cycle of debt followed by countries where they leverage their debt too much and we see the (all too frequently) ugly end of a Debt Supercycle. Rogoff and Reinhart offered data on those cycles.

I have been writing about US debt for decades. And the crisis has always remained in the future. And yet, we are now at almost $34 trillion of US government debt on our way to $60 trillion. Interest costs are beginning to significantly eat into the total revenues.

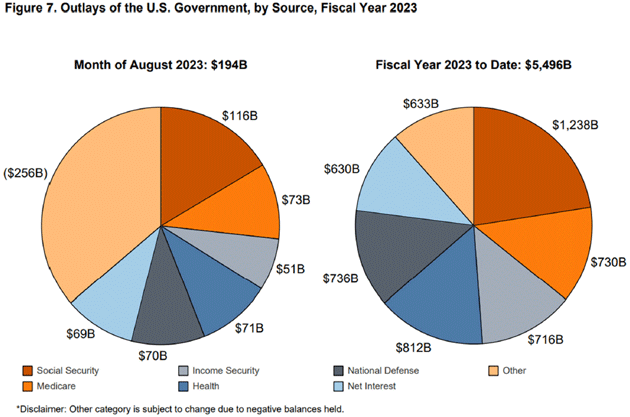

The most recent budget analysis from the US Treasury shows the net interest rate payments are getting close to total military expenses and will likely surpass that within the next few years. We will look at this more in depth over the next few weeks but let me just offer up a few charts from the Treasury website.

Source: US Treasury

Note that for the month of August net interest expenses were essentially equal to National Defense and larger than welfare (Income Security). Note that the average duration of federal debt is roughly 7 years. As longer-term paper with much lower rates rolls off, it is replaced with much higher-cost debt.

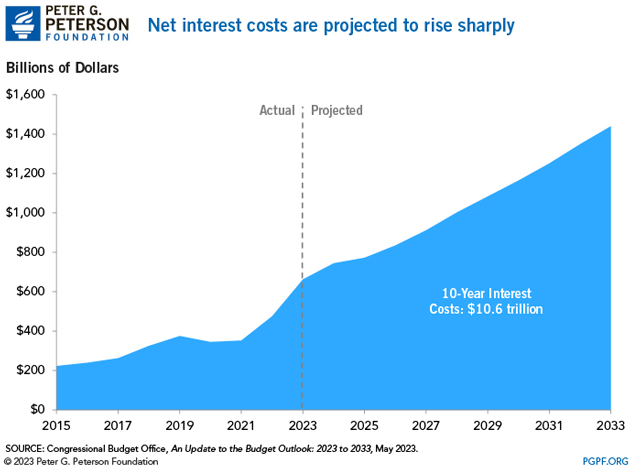

The next chart from the Peterson Foundation (well worth perusing—but remove sharp objects as you do, though!) illustrates that point. The chart shows that just a few years ago, total interest expense was in the $300 billion range. Today it is double that and projected to triple within four to six years. If interest rates continue rising it will be even worse.

Source: Peterson Foundation

We are on an unsustainable path. While CBO projections are obviously based on assumptions, what happens when we are at $50 trillion total debt (highly likely!) and interest rates are 4% (certainly possible if the Bond Vigilantes wake up from their long slumber, which might happen soon.)

I will be looking at this problem in depth over the next few weeks because we are in for a rough ride if an economic crisis erupts at the same time the other cycles reach their own conclusions. I think it is critical investors get a handle on what we are facing and also on how to adjust our own lives in order to make sure that we, our families, friends, and communities get through it.

Debt Be Not Proud

Debt represents future consumption brought forward in time. When you buy a house, for example, your future spending on other goods and services will fall because you have monthly mortgage payments. Ditto for cars or any other debt-financed purchase. Even if you go bankrupt, somebody absorbs that debt, and whoever it is will have less to spend on other things.

Again, debt isn’t bad in itself. Debt is useful if you can repay it and you spend the borrowed money productively. Often one or both is lacking. When this happens on a large scale, it has macro effects that contribute to the “debt supercycle.”

he Art of Liberty Foundation will be co-sponsoring a conference in Sedona, Arizona on November 3rd, 4th and 5th entitled: Liberty on the Rocks!

The conference brings together some of the leading lights in Liberty to discuss our current political situation and SOLUTIONS, including how to create local Liberty groups and Freedom Cells and how to move yourself out of organized crime’s crooked admiralty law system by correcting your status and standing. Friday night, there will be a VIP Dinner and concert Featuring Grant Prezence. Saturday we are at the Global Center for Christ Consciousness in Sedona for talks, workshops and a panel. There will be a Liberty expo with the ability to table. It is free for all on Saturday after 3:00 PM. Sunday we are taking folks for yoga and hiking in the most beautiful place on the planet. Get the details at