Ever Heard of the Reproducibility Crisis?

Why You Should Care That Most Published Studies Can't Be Replicated.

Imagine you get a prescription for a new medicine from your doctor.

Or you go to the store to purchase an over-the-counter drug.

We’ve all been there at some point in our lives.

We trust that those drugs are safe because they are backed by years of scientific research and have been through a rigorous regulatory approval process.

Now, what if it turns out that the data that was used to gain approval to enter into the clinical trials that led to the approval of those drugs cannot be reproduced? What would that mean?

Let’s go for a walk down one of the darkest halls in the history of science.

What do I mean by replication?

First things first, just what is meant by replication and how does it differ from reproducibility?

Replication is in many ways the cornerstone of true science. To confirm the results by repetition is essential. Environmental health scientists Stefan Schmidt summed it up as follows:

“It is the proof that the experiment reflects knowledge that can be separated from the specific circumstances (such as time, place, or persons) under which it was gained.” (Schmidt, 2009)

Without replication how do we know that the results aren’t entirely based on the biases of the scientists conducting them and the specific experimental systems whereupon they were conducted?

To have relevance it must be demonstrated that an experiment can be independently replicated outside of the original lab.

Simply put, replication is “the action of copying or reproducing something” (New Oxford American Dictionary). In this case the thing being reproduced is the experimental results.

At least that is the goal. Unfortunately, what follows in this article will show that for the majority of the time that is anything but the case.

In contrast, reproducibility is just about reproducing the same results from the same data set. Not trying to conduct the same experiment to see if you end up with the same data.

This is an important distinction to make before proceeding.

The CDC Said What?

In 2005, PLoS Medicine published the landmark essay by John Ioannidis whereby he shockingly claimed that “There is increasing concern that most current published research findings are false” (Ioannidis, 2005).

Say what? I thought we were supposed to trust the science, that it was settled. Might not want to jump on that until you’ve read the rest of this article.

While many, even a group from the CDC, agreed with Ioannidis’ notion they tried to come up with ways to salvage the smoldering wreckage of science that he presented.

The claim from the CDC was that replication was one of the best ways to increase the probability that a given research finding was true. Here is what they said:

“As part of the scientific enterprise, we know that replication—the performance of another study statistically confirming the same hypothesis—is the cornerstone of science and replication of findings is very important before any causal inference can be drawn.” (Moonesinghe et al., 2007)

You’re going to want to remember that last part about it being “the cornerstone of science”.

Several years later one of the greatest “hold my beer” moments in scientific history ensued when not one, but two biotech companies published their takes on what soon became known as “The Replication Crisis”.

What is The Replication Crisis?

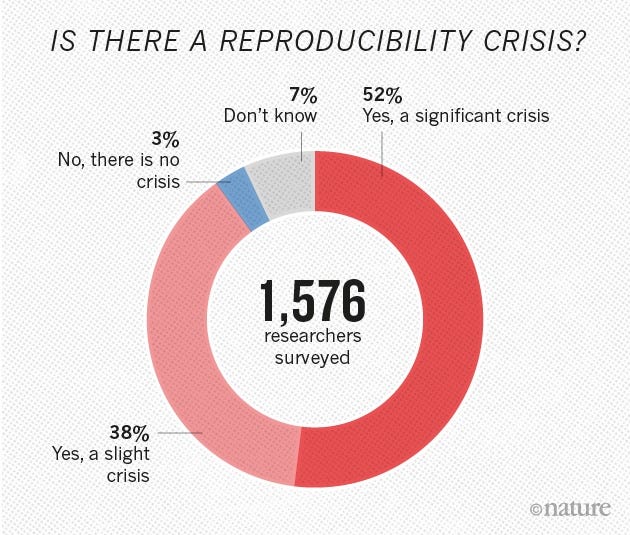

A series of events in the early 2010s kicked off what came to be known as The Replication Crisis. Largely, it was the realization that the inability to replicate published studies was not only widespread, but way beyond what most scientists would have ever expected.

Outside of my own personal experience as a scientist, there are three main pieces that I believe characterize this crisis and boy are they doozies.

It’s one thing if a hole in the wall academic lab somewhere in the middle of nowhere reported that their experiments couldn’t be replicated. I think we can all probably appreciate that.

What if it happened in the center of the biotech industry?

In the early 2010s two companies, Bayer Healthcare and Amgen, reported on a stunning lack of replication that occurred within the walls of their own labs.

Let me back up real quick because you might be wondering why in the world they undertook such an endeavor.

Well, most drug companies (pharma or biotech) strive to build and keep robust pipelines. In order to do this, they must either acquire new drugs or find ways to identify new targets to develop drugs against.

Development of pharmaceutical drugs is extremely costly in time, resources and perhaps most of all, the monetary investment. To mitigate that risk, many companies have put in place in-house new target validation teams.

Many new ideas for drug targets come from published studies so, it is important to validate them before making a further significant investment. No sense in moving forward if it's not valid, right?

Well, it was apparent that a significant number of published studies were not able to be replicated internally at Bayer so, they decided to put a number to it.

They conducted a survey of the scientists within their target discovery group. The results were quite revealing.

Bottom line, in only 20-25% of projects were the published data confirmed by in-house replication experiments.

That means upwards of 85% couldn’t be replicated. (Prinz et al., 2011)

The prestige or impact factor of the journal did not impact the reproducibility of the data. This confirmed what scientists at Bayer were seeing but, these findings were still shocking, nonetheless.

Not to be one-upped, Amgen came along and decided to conduct a study of their own to evaluate whether or not they were able to confirm the results of published findings in-house.

Unlike Bayer, they actually conducted the replication experiments and they stacked the deck in favor of replication by selecting 53 “landmark” studies with new findings all in the oncology field.

Own a piece of libertarian activist history! In 2013, the police accountability organization Cop Block produced a one-time run of "Shiny Badges" modeled after the Keene, New Hampshire police department badge from a manufacturer of "real" police badges. The heavy-weight badge features the Cop Block logo and the words: "Shiny Badges Don't Grant Extra Rights,” reminding the police of the incredible delusion required to believe a shiny badge gives one an exception from morality or the "right" to imprison peaceful people for victimless crimes among other immoral transgressions required for the job.

The Art of Liberty Foundation acquired Five (5) of these at PorcFest 2023, and we are auctioning these off to support the foundation. You can buy here for $250 OR "Go Paid" as a $250 Founding Member on SubStack to receive your shiny badge, an Everything Bundle, AND a One-Year Founding Membership on the Art Of Liberty Foundation's Important News Substack. These are the only Cop Block Shiny Badges available on the internet and when they are gone... They are Gone!

Go Paid (or Upgrade) at the $250 Founding Member level and get the Badge + an Everything Bundle + a One-Year Founding Membership to the Daily News & The Art of Liberty Foundation’s Important News Substacks.

Thanks for this. This sheds light on the current human race towards mediocrity istead of excellence. The "greatest generation" pursued excellence when faced with the existential crisis of their time (WW2...Duhhh-hh). Our current, obvious, race to mediocrity -- state mandated and voted upon -- is itself the existential crisis of our time.